Is waste-to-energy a waste of energy?

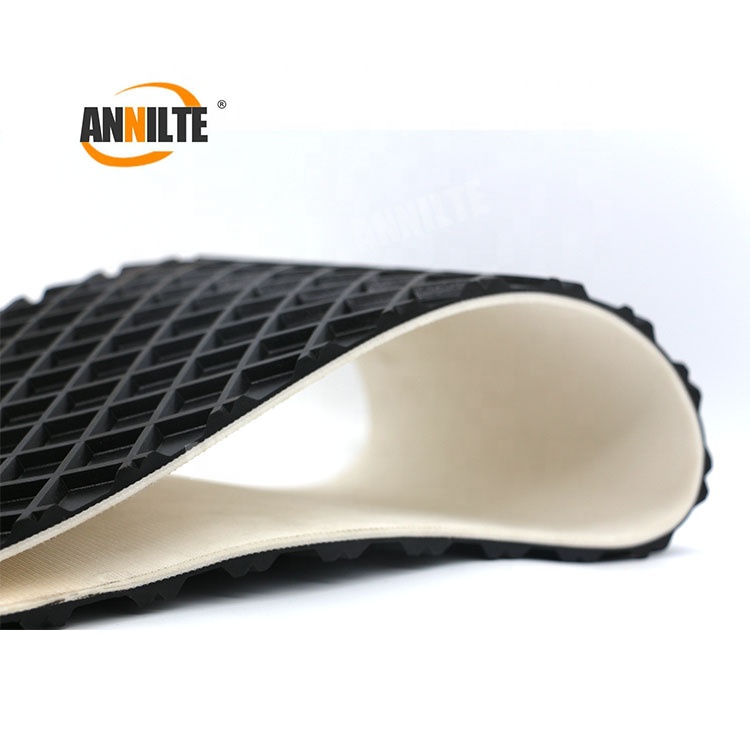

A Dorchester County farm's partnership with an Irish company is set to put that question to the test soon. PVC Conveyor Belt

Bob Murphy and his two sons, Brad and Justin, own 16 chicken houses in southern Dorchester. The postal address is Rhodesdale, but the closest town is Sharptown, which can be reached by a short drive south past a tangle of trees and over the high-arching bridge at the Nanticoke River.

It is like the postcard version of a Delmarva poultry operation. The manicured bushes and neat lawn rival the grounds-keeping of that of many a golf course. The driveway is a virtually pothole-free ribbon of crushed stone.

Murphy wears faded jeans and a long-sleeved collared shirt with the top of a pen visible in the left-breast pocket — the uniform of the modern farmer. He seems to take as much pride in running a clean farm as he does in raising productive flocks.

But it could be cleaner, he says.

He and many other Delmarva farmers are under greater pressure than ever to find alternatives to spreading manure on their fields as fertilizer. To help meet its federal obligations to cut nutrient pollution in the Chesapeake Bay by 2025, Maryland launched a so-called phosphorus management tool last summer aimed squarely at farmers.

Recently, trucks hauled 800 tons of chicken manure from Murphy's farm to another. He had no use for it himself because much of his land is fairly saturated with phosphorus, portions of it having been a dairy farm prior to his ownership.

Hauling the manure away, he said, is just a temporary solution in the new era of farming in the Free State.

"The farmer who bought that 800 tons, he's not going to keep being able to do that" because his own phosphorus concentrations are eventually going to rise as well.

The Ireland-based company has gained a foothold in the waste-to-energy business in Europe, where it has two commercial operations running in the United Kingdom and others in the pipeline, including a plant for agribusiness giant Cargill. Its partnership with the Murphys marks the company's first U.S. project.

Although he calls it a "demonstration project," commercial director Sean Fitzpatrick said he is confident his company's technology will be commercially viable and be widely adopted in its new country.

"The deployment of the Bhsl solution could resolve the problem of land spreading of poultry manure whilst securing the business of chicken growing in the Chesapeake region," Fitzpatrick said in an email response to The Daily Times' questions.

How it works: A conveyor belt drops the litter — the mixture of manure and bedding left behind on a chicken house's floor — into a large container. There, the litter is burned in a heated layer of sand suspended by jets of air.

The process creates heat that can warm chicken houses or be sold as electricity back to the power grid, The main byproduct is an ash that can be sold as fertilizer, Firtzpatrick said.

The project is among a handful of projects testing manure alternatives that have received state funding under a program that began in 2011. Then-Gov. Martin O'Malley's administration contributed nearly $1 million to the Murphy farm project in 2014.

“Investing in Maryland’s in-state renewable energy boosts our economy, ensures that we have abundant energy resources well into the future and creates more jobs and opportunity for more Marylanders," O'Malley said at the time in a statement.

The roster of experiments range from an anaerobic digester in Worcester County to a Perdue-sponsored bio-refinery in Wicomico. Despite millions in state subsidies, however, nothing viable has come of it so far.

Murphy plans to use the heat to replace the propane-fueled heaters in four of his chicken houses. Whatever he doesn't use, particularly during the warmer months, he plans to sell back to the power grid.

Farming is a third career for Murphy. He was a lineman for Delmarva Power and then a labor union representative before he retired in 1998. Looking for an investment he could pass on two his sons, he opened his first chicken houses in 2004.

After more than a year of planning, he expects construction to start on the power plant building by the end of the month. The plan is to have the system running by April. If it works, his chickens should grow better, too, because of the warmer and drier conditions inside the houses, Murphy said.

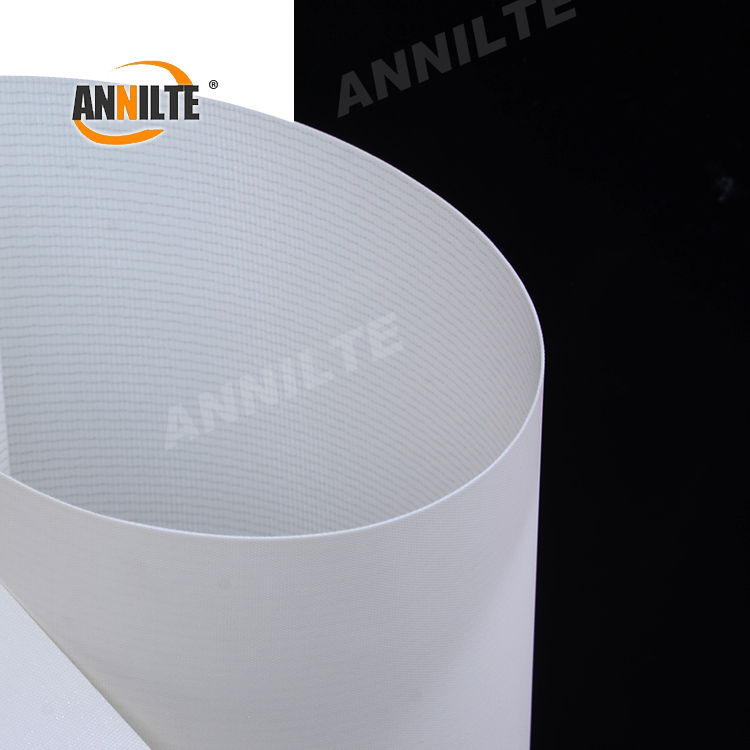

Nylon High Speed Belt "I just hope it works," he said.